Greg from Castro Valley writes: “Chris, I read that some protestors are suing President Trump because they were beat up at one of his campaign rallies last year. All he did was give a speech. He didn’t hit anyone. How can President Trump be sued?”

Greg, the President is subject to the laws of the United States, including the civil law, just like any other person in our society.

The case of Clinton v. Jones, 520 U.S. 681 (1997), made clear this is the law. In 1994, Paula Jones sued President Clinton for sexual harassment based on actions that allegedly occurred before he took office.

President Clinton asserted that litigation of a private civil damages action against a sitting President must in all but the most exceptional cases be deferred until the President leaves office. The U.S. Supreme Court rejected President Clinton’s claim, holding that a civil lawsuit against the President could proceed while the President was in office. As a result, President Trump, like any defendant in a civil action, can be forced to respond to requests for documents, submit to questioning by opposing counsel, testify at trial, and, should the plaintiff prevail, pay the judgment.

The lawsuit you are referring to Greg was filed in federal court in Kentucky by three persons who attended a Trump campaign rally in Louisville last year. As President Trump was speaking, they began to protest. President Trump told the crowd, “Get ‘em out of here.” In response, several attendees shoved and punched the protestors, forcing them to leave the rally.

The protestors filed a lawsuit for assault and battery by the individuals who physically attacked them. The protestors also named President Trump as a defendant. Their complaint alleges that President Trump incited the crowd to commit violence against them.

The President, like all Americans, possesses the right to free speech under the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. In its landmark decision of New York Times v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964), the Supreme Court explained that fundamental to the First Amendment is “the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.”

However, certain types of speech, including so-called “fighting words,” are so lacking in value that they do not receive protection under the First Amendment. The Supreme Court has stated, “Fighting words are not a means of exchanging views, rallying supporters, or registering a protest; they are directed against individuals to provoke violence or to inflict injury.” The classic example is the person who falsely shouts “fire” in a crowded theater. The First Amendment does not bar the individual’s prosecution for setting off a panic.

The “fighting words” exception to the right to free speech is narrow. Speech solely advocating the use of force or violence is insufficient to lose protection under the First Amendment. Instead, the Supreme Court held in Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969), that a three-part text must be satisfied: (1) the speech explicitly or implicitly encouraged the use of violence or lawless action, (2) the speaker intended that his or her speech would result in the use of violence or lawless action, and (3) the imminent use of violence or lawless action was the likely result of the speech.

President Trump’s lawyers sought to have the protestors’ lawsuit dismissed on the basis that his statement (“get ‘em out of here”) was protected speech under the First Amendment.

The federal judge denied the motion. The judge held that the plaintiffs adequately alleged that President Trump’s statement constituted an incitement to the crowd to commit violence. In reviewing the complaint, the judge found numerous factual allegations supporting an inference that the President Trump’s statement to “get ‘em out of here” was directed at audience members to use force against the protestors.

Did President Trump intend for his statement to result in violence? In addressing this question, the complaint alleged multiple occasions before and after the Louisville rally when President Trump made comments endorsing or encouraging violence against protestors. The judge found that the complaint sufficiently alleged that President Trump knew or should have known that his statement at the Louisville rally would result in violence.

Greg, the judge did not decide the merits of the case. The judge was only evaluating whether plaintiffs’ claims against President Trump contained sufficient factual allegations to allow the lawsuit to proceed. The plaintiffs will now gather evidence (called discovery) which could include questioning President Trump under oath.

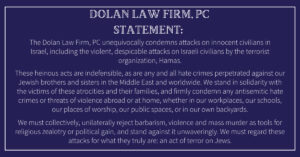

By Christopher B. Dolan, owner of the Dolan Law Firm. Email Chris your legal question to help@dolanlawfirm.com.