This week’s question comes from Aimee F. in Seacliff, who asks,

Q: “I read in last week’s paper that Amazon and other companies are developing robots which will be delivering packages door to door. They look like big ice-chests on wheels. This makes me concerned. My elderly mother does not see well but walks alone between her house and the grocery store. I am afraid she wouldn’t see one of these robots, as it is the last thing she would expect to come across on the sidewalk. If someone gets hit or falls over because of one of these robots, who would be held responsible?”

A: Thanks for your question, Aimee. As you read, Amazon recently publicized that it would be testing ”Scout,” its delivery robot, in Snohomish County, Washington, for delivery of expedited orders (same day to two day) to its Prime members. Designed for the “last mile” of the delivery cycle, the robots will travel to residences using sidewalks. For the near future, the robots will only deliver during daylight and must be accompanied by humans who can intervene if a robot does not navigate well around pets, toys, kids, cars, pedestrians, etc.

Amazon is not the first company to venture into robot delivery. In 2014, a San Francisco company called Starship, founded by the founders of Skype, introduced its robot delivery service, which now boasts over 100,000 km of ground covered and 30,000 deliveries. Both Starship and Kiwi, a company founded in Berkeley in 2017, have launched pilot robotic delivery services to students on college campuses around the country. Marble, another San Francisco company founded in 2015, makes food deliveries for Eat24 in the Potrero and Mission Neighborhoods. Postmates has also been developing a robot, Serve, with a mission to “respect cities, meet customer demands, and help local businesses sell even more.”

In December 2017, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed Ordinance 244-17, amending Public Works Code Section 794. Originally, the ordinance was drafted as an outright ban on robotic delivery vehicles, also known as Automated Delivery Devices (“ADD”). The prohibition failed to secure the required number of votes, so it was replaced by a permitting process that allows testing of up to 9 ADD’s total at any one time, with no single company having more than 3 on the road. Testing has been limited to certain neighborhoods in zoning districts designated for Production, Design and Repair (“PDR”) and ADDs are restricted to traveling no more than 3 miles per hour with human accompaniment at all times.

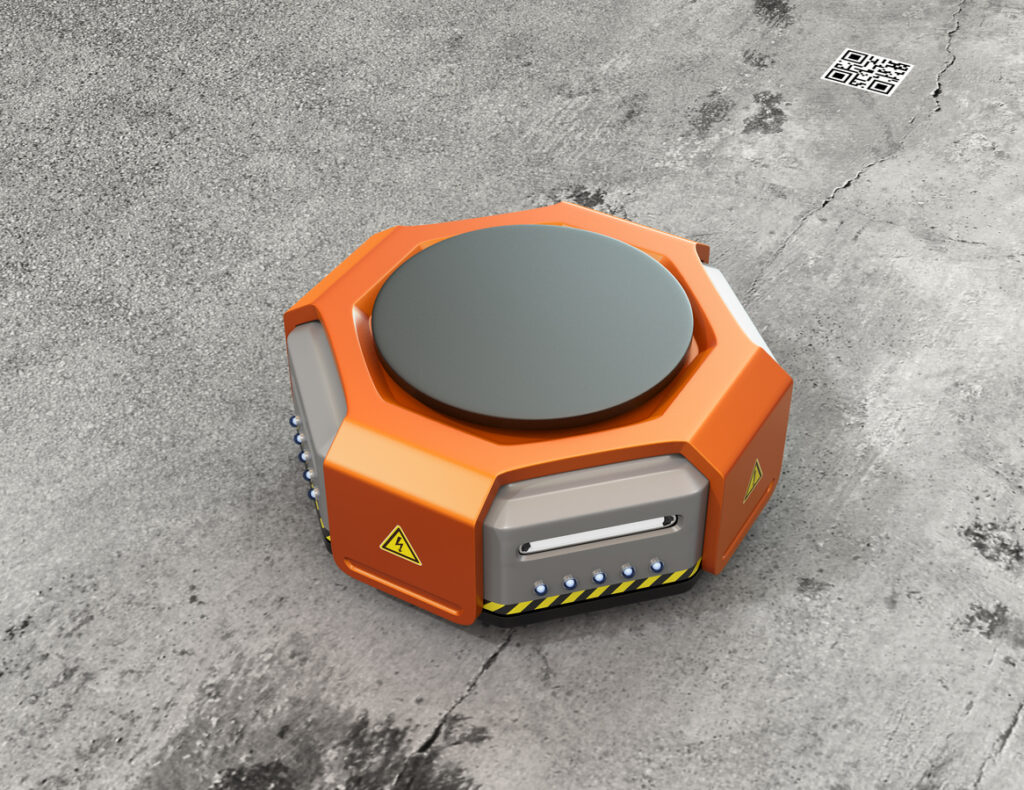

As to your question: what does the law say about responsibility for injuries caused by ADDs? California law provides that an injured bystander like your mother may bring suit for her injuries under negligence or strict products liability claims. Strict products liability would be brought against the designer and manufacturer of the robot, as well as the permit holder, alleging the robots are defective and dangerous due to their design and/or manufacturing process. For instance, an injured party could argue that, given that ADDs are below waist-height (for the most part), a reasonable person would not expect such a novel and diminutive vehicle on the sidewalk or crossing the road, any design lacking a conspicuous marking such as a flag or some other item would cause unlawful danger to pedestrians and motorists.

An injured party could also sue under negligence law to hold an ADD’s permit holder accountable for making sure the robot functions in a reasonably safe manner. Therefore, the permit holder would be liable for any harms caused by the robot if its actions do not meet this “reasonably safe” standard. There is no developed case law so far directly involving ADDS, so the most analogous decisions would be those evaluating the behavior of pedestrians, bikes, skateboards, etc. One thing yet to be worked out, is whether the permit holder would have to provide the data collected by the robots’ myriad sensors to a party claiming injury due to the alleged negligent operation of the ADD.

While the exact nature of injuries, claims and lawsuits from this new technology is yet to be determined, odds are, unfortunately, that someone will be hurt or killed. I wrote in 2012 about the inevitability of Uber’s systems and drivers causing injury or death, a prediction that manifested tragically with the death of 7 year old Sophia Liu whose family I represented in the first wrongful death lawsuit in Uber’s history. Sophia’s family and I went to Sacramento and helped pass a bill that requires Uber to carry a million dollars in insurance. I hope that, in this case, the companies are more deliberate and resolve issues concerning liability and insurance before the inevitable moment when someone is hurt or killed.