Remembering United States v. Wong Kim Ark

Written by Mari Bandoma Callado, Dolan Law Firm’s Senior Associate Attorney & Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Director

The Dolan Law Firm recognizes Asian American & Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month and celebrates the achievements and contributions of the AAPI community to American history, culture, and society.

During the coronavirus pandemic, the rise in violence against AAPIs put a spotlight on the fact that AAPIs have long been the targets of racism and discrimination in the U.S., including through the law. Throughout history, AAPIs stood up against unjust laws and fought for significant constitutional protections.

United States v. Wong Kim Ark is a landmark case that established birthright citizenship based on location through its interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment and stated that anyone born in the U.S., excluding those born to diplomats, would be granted U.S. citizenship, regardless of the standing of their parents.

Background

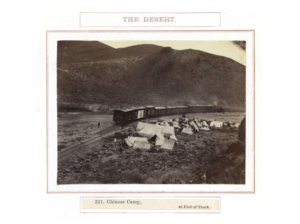

In the 1850s, Chinese workers migrated to the United States, first to work in the gold mines, but also to take agricultural jobs, and factory work, especially in the garment industry. Chinese immigrants were particularly instrumental in building railroads in the American west – over 10,000 Chinese laborers worked to complete the transcontinental railroad between 1863 and 1869.

Alfred A. Hart photographs, 1862-1869

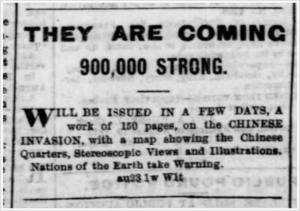

Despite their contributions to the transcontinental railroad and agriculture, Asians, especially the Chinese, were the target of racial discrimination in the mid-to-late nineteenth century.

In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act which banned the immigration of Chinese laborers to the U.S. for ten years. This was the first immigration law that prevented immigration and naturalization based on race and nationality. In 1892, the Chinese Exclusion Act was extended for another 10 years by the Geary Act and it became permanent in 1902. The Chinese Exclusion Act was not repealed until 1943.

United States v. Wong Kim Ark

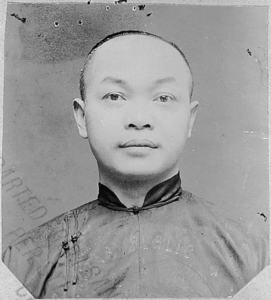

- Wong Kim Ark was born in 1873 in San Francisco to Chinese parents who were legally domiciled residents of the U.S.

- He visited China in 1894 and was denied re-entry in 1895 due to the Chinese Exclusion Act.

- He applied for a writ of habeas corpus and claimed that he was a natural-born U.S. citizen.

- The United States argued that since he was born to Chinese parents who were subjects of the emperor of China, then he was also a Chinese person and a subject of the emperor of China.

- The District Court agreed with Wong Kim Ark – that he was a U.S. Citizen and therefore exempt from the Chinese Exclusion Act.

- The United States appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

- In his Supreme Court case, Wong argued he was a U.S. Citizen under the 14th Amendment which declared “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States, and of the State wherein they reside” and therefore should be permitted entry to the U.S. since the Chinese Exclusion Act doe not apply to him.

- Originally, birthright citizenship was meant to benefit persons of African descent, and formerly enslaved African Americans in particular. But the question is whether that principle applies to all people regardless of race—and the case goes all the way to the Supreme Court.

- The U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed his claim to citizenship, and since his citizenship was constitutionally protected, the Chinese Exclusion Act and other congressional acts did not apply and cannot override the Constitution. The Court’s decision defined the parameters for jus soil ensuring the citizenship of children born in the U.S. to non-citizen parents. The concept is popularly known as birthright citizenship.