By: Mari Bandoma Callado, Eric St. John & the Dolan Law Firm DE&I Committee

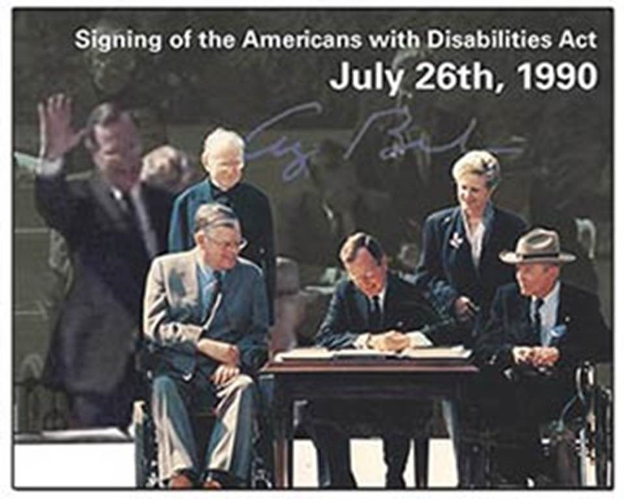

32 years ago, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was signed into law, making it unlawful for private employers, state/local governments, employment agencies, labor organizations, and labor-management committees to discriminate against qualified individuals with disabilities. Under the ADA, employers with fifteen or more employees cannot discriminate against qualified individuals with disabilities.

A person with a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits a major life activity is “disabled” and protected by the ADA. Major life activities are basic functions and may include: seeing, sleeping, learning, hearing, breathing, thinking, speaking, concentrating, reproduction, performing manual tasks, walking, interacting with others, sexual relations, caring for oneself, standing, reading, and working. It also includes bodily functions, such as normal cell growth, or the functioning of the respiratory, circulatory, cardiovascular, endocrine, immune, and digestive systems.

Disability discrimination occurs when an employee is treated differently at work because of their disability, perceived disability, or association with a disabled person. The ADA makes it unlawful to discriminate in all employment practices such as recruitment, pay, hiring, firing, promotion, job assignments, training, leave, lay-off, benefits, and all other employment-related activities.

The History of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

began far before July 26, 1990 when people with disabilities began to challenge the social barriers that excluded them from their communities, and when parents of children with disabilities began to fight against the exclusion and segregation of their children. It is important to recognize the uphill fight that generations past have endured to secure the rights for people with disabilities.

The ADA is one of America’s most comprehensive pieces of civil rights legislation that prohibits discrimination and guarantees that people with disabilities have the same opportunities as everyone else to participate in the mainstream of American life — to enjoy employment opportunities, to purchase goods and services, and to participate in State and local government programs and services.

Olmstead v. L.C.

The landmark decision in Olmstead v L.C. was one of the first uses of the ADA to protect individuals unnecessarily held in a psychiatric unit. Two women (L.C. and E.W.) with mental disabilities were confined in a psychiatric ward for years prior to this decision.

In 1992, L.C. was voluntarily admitted to Georgia Regional Hospital at Atlanta (GRH), where she was confined for treatment in a psychiatric unit. By May 1993, her psychiatric condition had stabilized, and L.C.’s treatment team at GRH agreed that her needs could be met appropriately in one of the community-based programs the State supported. Despite this evaluation, L.C. remained institutionalized until February 1996, when the State finally placed her in a community-based treatment program, 3 years after doctors said her needs could be met outside of the psychiatric unit.

E.W. was voluntarily admitted to GRH in February 1995; like L.C., E.W. was confined for treatment in a psychiatric unit. In March 1995, GRH sought to discharge E.W. to a homeless shelter, but abandoned that plan. By 1996, E.W.’s treating psychiatrist concluded that she could be treated appropriately in a community-based setting. She nonetheless remained institutionalized until a few months after the District Court issued a judgment in the Olmstead v. L.C. case in 1997.

Both E.W. and L.C. were held for years of their life, even after doctors had suggested community based settings for treatment. The only reason they were allowed to re-enter their communities was because they successfully brought a lawsuit under the ADA to protect their rights against discrimination.

The two woman brought suit under Title II of the ADA arguing that unnecessary institutional segregation constitutes discrimination. The U.S. Supreme Court found that the unjustified segregation of people with disabilities is a form of unlawful discrimination under the ADA and both E.W. and L.C. were able to finally be released from their psychiatric units in 1996 and 1997.

Following the landmark decision, individuals with disabilities can demand they be provided with services for their disability in the most integrated setting appropriate to their needs.

The Court held that states are required to provide community-based services for people with disabilities who would otherwise be entitled to institutional services when:

-

(a) such placement is appropriate;

-

(b) the affected person does not oppose such treatment; and

-

(c) the placement can be reasonably accommodated, considering the resources available to the state and the needs of other individuals with disabilities.

Individuals with disabilities have the right to dictate their life and treatment. Being institutionalized for mental disabilities is common in America. Following Olmstead v. L.C. many individuals have avoided unnecessary institutionalization and are now receiving services in their own communities.

Individuals with disabilities now have greater control over their community-based care and services. Individuals’ needs are met by providing reasonable accommodations in their communities, and not by moving to a more restrictive setting.

The stories of L.C. and E.W. are stories of bravery and courage. Thanks to their fight many Americans today do not have to face institutionalization by the State. Unfortunately though, institutionalization still occurs and individuals with disabilities are still discriminated against. We highlight this case and these individual’s stories to remind us all that the fight must continue and change is not made in one day. There is no place for discrimination in our society and it takes each and every one of us to make the changes necessary for everyone to have their rights upheld and protected.

To be protected by the ADA, an employee must disclose their disability to at least one person who represents the employer, such as a supervisor or human resource person. While the employee does not have to share every detail about their disability, they do need to provide enough information to show that they have a “disability” under the law and that they need accommodation.

If you believe that you have been discriminated against and/or harassed because of your disability, perceived disability and/or association with someone with a disability, contact our disability discrimination lawyers today.